History of Butoh

"An Art Form In Transition"

(The following article by Don McLeod

originally appeared in Melt Magazine in a slightly different format.)

Butoh is an avant garde performance art, that has its origins in Japan

in the 1960's. After the second world war, Japan was a country in transition.

It was a country still holding onto its old world traditional values while

being forced into western democratic values by America's conquest. During

this time there was much student unrest and protest.

Theatre groups were performing socially challenging pieces, and there were daily demonstrations in the streets. Butoh was born out of this chaos.

Its founders were a young rebellious modern dancer named Tatsumi Hijikata (1928 -1986), and his partner Kazuo Ohno (b. 1906).

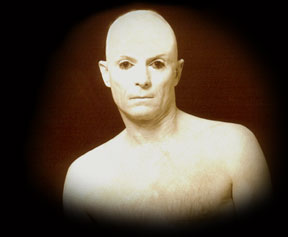

Hijikata was dissatisfied with the Japanese modern dance scene, feeling that it was merely a copy of the work being done in the West. He wanted to find a form of expression that was purely Japanese, and one that allowed the body to "speak" for itself, thru unconscious improvised movement. His first experiments were called Ankoku Butoh, or the Dance of Darkness. This darkness referred to the area of what was unknown to man, either within himself or in his surroundings. His butoh sought to tap the long dormant genetic forces that lay hidden in the shrinking consciousness of modern man.

His first public performances were wild, primal and sexually explicit. They quite naturally shocked the conservative Japanese dance community, and he was banned from appearing at future organized events. This was the spark that gave birth to butoh. Many of Japan's dancers, poets, visual artists and theatre performers rallied around this exciting and dangerous new art form. Underground performances became increasingly popular, and soon there were numerous groups being formed in the Tokyo area. Musicians, photographers and writers including Japan's leading novelist, Yukio Mishima joined Hijikata to collaborate on spectacular underground performances.

Butoh loosely translated means stomp dance, or earth dance. Hijikata believed

that by distorting the body, and by moving slowly on bent legs he could

get away from the traditional idea of the beautiful body, and return to

a more organic natural beauty. The beauty of an old woman bent against

a sharp wind, as she struggles home with a basket of rice on her back.

Or the beauty of a lone child splashing about in a mud puddle - this was

the natural movement Hijikata wanted to explore. Hijikata grew up in the

harsh climate of Northern Japan in an area known as Tohoku. The grown-ups

he watched worked long hours in the rice fields, and as a result, their

bodies were often bent and twisted from the ravages of the physical labor.

These were the bodies that resonated with Hijikata. Not the "perfect"

upright bodies of western dance, or the consciously controlled movements

of Noh and Kabuki. He sought a truthful, ritualistic and primal earthdance.

One that allowed the performer to make discoveries as she/he created/was

created by the dance.

It is easy to see how this dance, done in a trance-like state, on bent legs with rolled up eyes was disconcerting to the conservative Japanese modern dance community. But the work was soon to sweep the imagination of many younger artists, and by the 1970's butoh began to gain world-wide attention, as groups such as Sankai juku and Dairakudakan were invited to perform internationally. Today there are a number of groups and solo artists performing in North America, with artists in Seattle, San Francisco and Los Angeles, New York, Vancouver and Toronto.

Butoh has tremendous value as a training method for artists of other disciplines as well. In a year-long experiment at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in Hollywood, I worked with 2nd year acting students using butoh training methods to help unveil their natural expressiveness. We stripped away the socially acceptable movements and gestures, and encouraged the students to find and embrace hidden movements that lie buried beneath years of conditioned behavior. We bent the legs to view the world from a lower level, as might be considered by plants, animals and children. We purposely distorted the face, to keep out the natural desire to make the right expressions, or to give a calculated appearance. When the body is freed of its social constraints ...... amazing things begin to happen. Hijikata often trained his dancers thru the use of images. He would use give the students surreal images and have them react to them, thus stimulating the body and the subconscious to respond. Examples would be: Butterflies are landing on your right arm, your left arm is covered with cockroaches. Or you are walking in mud and your eyes are on the back of your head. We used music or more specifically sound design creations by artists like Robert Rich, Tuu and Lustmord, to provide an other-worldly vista of auditory inspiration. The results we sudden and dramatic. Almost every student found within themselves a way of moving truthfully, and created many dramatic, original and emotionally charged improvisations. Hidden elements of ones personality also tended to surface during these experiments. These awakenings to the true nature of self proved extremely beneficial to their development as consciously aware human beings, and to the craft of acting as well.

Another aspect of butoh, that I find especially appealing is that every

"body" is a perfect body. Meaning we are not so concerned as

to whether or not the student has a perfectly fit and lithe body of a

trained dancer, but rather that s/he finds organic expression through

the body they have now. Most ballet and jazz dancers are sadly sent to

pasture in their mid-thirties, and are soon passed over for younger more

physically capable models. With butoh the mature body brings as much or

more to the performance as does the youthful body. A prime example is

the afore-mentioned Kazuo Ohno, who is now 96 and still performing with

a vibrant inner intensity. His withered, aged body is his canvas and he

paints with great beauty upon it. Least it sound like butoh is less an

art form, than a therapeutic exercise, one must consider that butoh does

have its techniques; strength, flexibility and balance are vital components.

We learn to become one with the "other". Butoh is a hybrid form

of art, incorporating elements of theatre, dance, mime, Noh, Kabuki and

at times the Chinese arts of Chi kung and Tai chi. It is up to the individual

artist to find their own dance. But it should be a "dance" of

discovery, rather than a calculated series of movements meant to manipulate

the audience into a desired response.

Hijikata's first dances were often grotesque, twisted, dark and perverse. Ohno's butoh is more ethereal and floating, ever reaching to the light. Sankai juku are highly refined and tightly choreographed with their polished, other worldly movements of cat-like aliens. Or the masters of pure spectacle ... Dairakudakan with their sensual, imagistic and highly theatrical happenings. Butoh is ever-changing, and is here to stay. Because it gives us a halted, reverberating picture of our muted struggle to be human in this technological age of the disenfranchised body.

Butoh was formed by an amalgamation of influences. The German expressionistic dances of Mary Wigman and Harald Krautzberg gave butoh its creative freedom. Western writers such as Genet, Artaud and de Sade were read by butoh groups. Surrealism and Dada were another source of inspiration. Ohno was influenced by Marcel Marceau and especially by the passion of a Flamenco dancer named La Argentina, who he first saw in 1923 when he was a young boy. Some modern butoh performers have come from the dance world, others such as myself from theatre, or more specifically from mime. One the greatest butoh performers, and protege of Hijikata was Yoko Ashikawa, who had no previous theatrical or dance experience. Today a great variety of styles and aesthetics can be found in butoh. It has ceased being an exclusively Japanese art-form and is developing all over the world.

Copyright 2002, Don McLeod, All rights

reserved.